The story of owners Charles and Willa Bruce is another example of how hardworking black homesteaders were robbed in their “pursuit of happiness” by white supremacist hatred, bigotry and jealousy.

Race massacres that took place at Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 and Rosewood, Florida in 1923 are among such real American stories white-washed from history books that have sparked debates as to whether they should now be included in classroom curriculum (Critical Race Theory) to reveal a more complete history of America’s good, bad, beauty and ugly. This nation must confront the truth of its past before it can overcome it.

MORE NEWS ON EURWEB: Tamron Hall Show Executive Producer Candi Carter Quits Due to Toxic Set

The following story – Harry Smith’s Fifty Years of Slavery – is an authorized reprint from author and Michigan historian Larry Massie’s book volume, Pig Boats and River Hogs. The story gives detailed accounts from Smith’s autobiography published in 1891 and serves as a testament to the unthinkable horrors of physical and psychological hardships blacks endured with far-reaching generational, socially embedded reverberation in their quest for freedom, dignity and equality.

Harry Smith’s Fifty Years of Slavery

[He was “a long, lean, lantern-jawed, lobered-mouthed, high-cheeked Englishman, knock-kneed and club-footed, with no hair on his head, and lived about four miles west of Reed City (Michigan).”

Those faults notwithstanding, he might have continued to enjoy his peaceful mug of beer in a fashionable Reed City saloon had he not also been a loud-mouthed bigot. “You, you nigger, come here, come here nigger, come here,” he bawled across the bar, addressing Harry Smith.

Smith, who had spent 50 years in slavery in Kentucky among overseers who made Simon Legree look like Santa Claus, was not about to take that insult – not in Michigan anyway. Raising a heavy bar stool over his head, Smith told him that if he opened his mouth in such a way again, he “would smash him into the floor and never stop to sharpen him.” The bigot became a believer and never bothered Smith again.

Smith described that incident, as well as how he made short work of several other Reed City racists, in an autobiographical volume published in Grand Rapids in 1891. But the major portion of his 183-page Fifty Years of Slavery in the United States of America records the horrors of that “peculiar institution” as witnessed by Smith.

Born into slavery in 1815 in a weaving loom shed on a plantation in Nelson County, Kentucky, Smith was one of 18 siblings. His mother, a pious Catholic, saw to it that all her children were christened in the local Catholic church. Her religion, however, did not protect her from being treated in a most barbaric manner of the white man who owned her.

One of Smith’s earliest memories was of crying and begging the master not to kill his mother as, tied to a tree in front of the house with her clothing stripped from her body, she received 100 whip lashes, each one drawing blood. Her offense had been to take a 10-minute rest break while cutting corn.

Her punishment was light compared to that meted out to an old slave on the neighboring Ray plantation who had run away and been captured. Uncle George, as he was called, “was stripped naked, bound in the henhouse directly under their droppings, taken out, received 100 lashes from Ray, the same from his son, and placed back under the roost naked, face up. The next morning, (he) received the same with his flesh all lacerated, was bound to a shovel plow to cultivate tobacco, compelled to do a hard day’s work.”

Another nearby slave master named Edward Brisco won a well-deserved reputation for his cruelty. His philosophy was: “It didn’t matter how good they were, they must be whipped once a year to let them know they were negroes.” To prove his point, a few days before one Christmas, he had two of his loyal slaves, each more than 70 years old, stripped, bent over a barrel and given 50 lashes for no offense whatsoever. Other plantation owners frequently sent him slaves who gave their behavior problems for punishment.

Perhaps the most fiendish of the many Kentucky slave owners described by Smith was David L Ward, the “hell hawk.” He owned 300 slaves who worked his extensive salt manufacturing plant. Once, when he discovered a few pounds of salt had been left to burn on the bottom of a kettle, he bashed the slave responsible on the head with a shovel, then pitched him into the furnace to burn to death. His old slaves witnessed him “at different times, burn up in his furnace 15 colored people.”

The actual murder of slaves, those able to work, anyway, was evidently a rare occurrence. With an individual slave worth $2,000 or more on the market, they were too valuable a commodity to be destroyed. Oftentimes, slaves were rented out to those who needed extra labor. If someone killed a slave belonging to another he could be sued for damages – the value of the slave reckoned at the going rate per year times his expected lifespan. The murder of a young slave might cost a killer several thousand dollars.

Normally, according to Smith, if whipping or other cruel punishment did not bring unruly or insubordinate slaves under control, they were sold down the river to New Orleans, a fate greatly feared by Kentucky slaves.

Smith’s own 50 years spent as a slave were happier than most. Following his cruel master’s death, he was acquired by Master and Mrs. Jake Salone, who treated him kindly. That Smith was a hard worker who seldom incurred their displeasure also helped.

Several times during forays to visit girlfriends on neighboring plantations, however, he ran afoul of vigilantes known as” patrollers.” They would capture and whip any slave out and about without a written pass from his owner, Smith, who was known as the fastest runner in the county, successfully eluded patrollers on several occasions, although once, a vicious bloodhound nailed him. He carried the scars from that close call to his dying day.

In 1861, Smith’s white countrymen went to war to determine whether slavery would continue. He witnessed many atrocities committed by the guerrilla bands that roamed Kentucky during the succeeding four years. He assisted in burying 50 slaves, for example, who were gunned down while in route to the Union lines. Smith risked his own life to assist Union stragglers and parolees in hiding out from the bloodthirsty guerrillas.

Then, one morning in 1863 following President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Smith’s master walked in while the slaves were eating breakfast, steadied himself against the table and sadly announced:

“Men and women hear me, I am about to tell you something I never expected to be obliged to tell you in my life, it is this: it becomes my duty to inform you, one and all, women, men and children, belonging to me, you are free to go where you please.” Never had a scene been witnessed on the plantation to rival the resulting freedom jubilee.

After the war, Smith and his family moved to a farm 12 miles north of Indianapolis, where he sharecropped for a white landowner. In 1872, while on a hunting expedition, he first visited Reed City, a frontier settlement then known as Todd’s Slashing. Although few of the settlers there had ever seen a black man before, Smith soon won acceptance through his great sense of humor and warm personality.

He bought a lot and the following March moved to Reed City with his family. Times were tough, but he earned a living cutting cord wood while his wife and daughter set up a laundry business. Two years later, they had saved $50, enough to make a down payment on 20 acres of wilderness land located three and one half miles north of town in Lincoln Township.

Smith built a house and gradually cleared his homestead while his family continued to do laundry, which Smith carried in large baskets on his head back and forth to Reed City. Eventually, he succeeded in paying off his farm and in erecting a dance hall, 100 feet long.

For many years, settlers for miles around flocked to Smith’s dance hall to “trip the light fantastic toe” to the tune of his tambourine and to listen to his amazing stories of 50 years of life in slavery.] Author and Michigan historian Larry B. Massie resides in Allegan, Michigan. Email: [email protected]

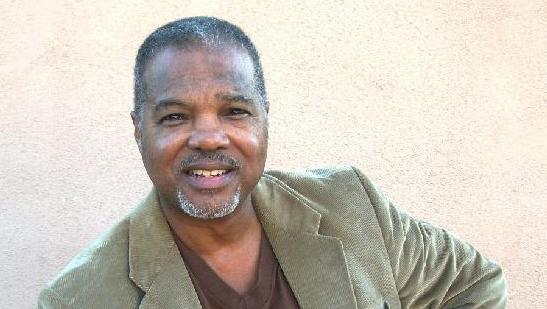

Larry Buford is a Los Angeles-based contributing writer. Author of “Things Are Gettin’ Outta Hand” and “Book To The Future” (Amazon); two insightful books that speak to our moral conscience in times like these. Email: [email protected]

We Publish News 24/7. Don’t Miss A Story. Click HERE to SUBSCRIBE to Our Newsletter Now!