*Ganiyu Jimoh (a/k/a Jimga) – The blockchain technology has come to disrupt the way we frame, interrogate, and contextualize digital art globally.

Ganiyu is a scholar, cartoonist, activist, and digital artist. He holds a Ph.D. in Visual Arts from the University of Lagos, Nigeria, where he has taught graphic design, cartooning, and art history courses.

He has received international awards for his scholarly contribution to African art and political discourse. He was a recipient of the African Studies Association Presidential fellowship award in the United States of America in 2019 and a Post-doctoral Fellow with the Arts of Africa and Global Souths research programme, Department of Fine Art, Rhodes University, South Africa, in the same year.

As a scholarly writer and a practicing political cartoonist, Jimga (as he is professionally known) has several local and international academic publications and exhibitions to his credit. Ganiyu is currently on his second doctoral research in digital art and animation in the United States of America. I had the opportunity to interview him

MORE NEWS ON EURWEB: Director Sacha Jenkins Unpacks New Louis Armstrong Documentary ‘Black & Blues’ | Watch EUR Exclusive

TAYO: Let’s begin with the basics. Why cartoon as a practice and as a scholarly endeavor?

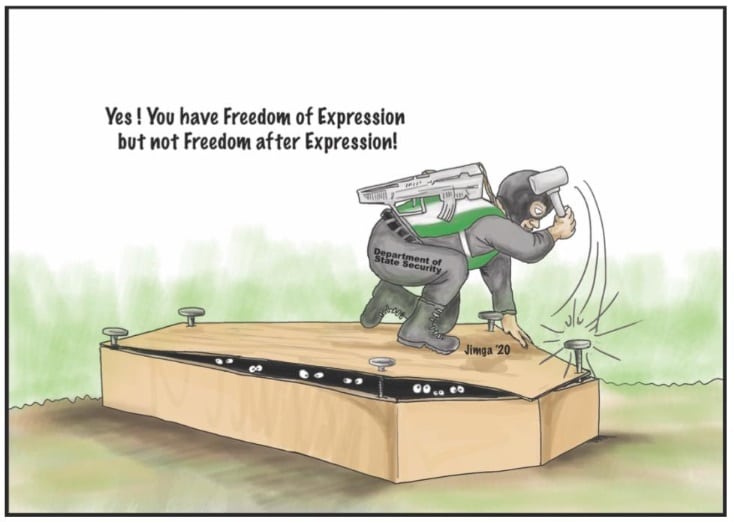

Jimga: I started creating cartoons as a form of intervention on socio-political issues in my society right from a tender age. I believe in active participation in correcting societal ills, and

the art of cartooning provides a platform to critically engage with larger members of society through the mass media platform of prints and the internet.

The medium is quicker, faster, louder, and easier to decipher by the public. I see cartoons as a means of taking an artistic obligation to correct societal ills. My scholarly works on cartooning also foreground the medium as a democratic art form, handy in interrogating socio-political issues and serving as visual historical texts.

I embarked on a scholarly exploration of cartooning during my master’s program because I wanted to connect with political cartoons’ theoretical underpinnings and historical development as a distinct art form. The preliminary research exposed the dearth of scholarly research in this area of study, as most literature on cartooning is either about western cartoons or African cartoons explored within the western analytic framework. That sparked a great interest which is still very much alive to date. I have been able to theoretically engage African political cartoons and devised frameworks through which they could be analyzed within the Afrocentric paradigm.

TAYO: Some of your works on returning Benin artefacts from Western Museums to Nigeria have been gaining global attention. What was the motivation behind this, considering the fact that these works were produced about twelve years ago?

Jimga: Apart from the general consciousness of the fact that most of what we could call our collective heritage as people are not within our reach and stacked “behind bars” since the days of slavery and colonialism, I got fully involved in the repatriation debate during my postgraduate studies as part of my graduate seminars and research. Incidentally, in 2010 during my studies, my advisor conveyed the first significant symposium and exhibition on the repatriation of Benin artefacts at the University of Lagos tagged Benin1897.com. This provided the necessary impetuous for me to visually engage with the subject matter through cartoons. I produced the work titled “Double Standard,” which addresses the restitution question against the backdrop of imperialism, neocolonialism, and migration as part of my artistic reflection on the central issues. Since then, the piece has been interrogated in at least ten scholarly publications from five countries and featured in twelve exhibitions in Nigeria and abroad. It is currently in a group exhibition titled “In a Pot of Hot Soup” at the Brunei Gallery, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, UK. Despite being produced in 2010 on the subject of Benin artworks stacked in Western museums, its core agency manifests within a multilayered level of mediation.

TAYO: Many people believe that traditional art should remain with the traditions and should be kept in the museums as relics of the precolonial period since ways of life have significantly changed. Do you share the same opinion as a contemporary artist? Do you think contemporary art has anything to gain from tradition?

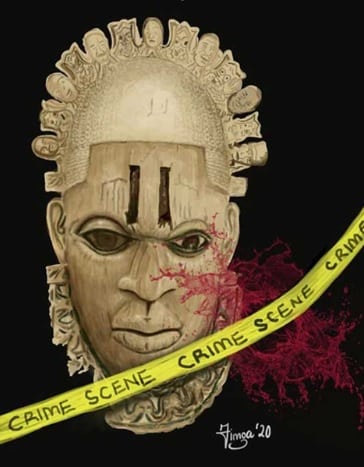

Jimga: For me, contemporary art is always in dialogue with tradition, as the past is never detached from the present in which the future emerges. The contemporary has always been, consciously or subliminally appropriate, recontextualize and or repurpose traditions. We shouldn’t forget that the so-called “tradition” was once contemporary in a given period. So, nothing is bound to a fixative state – reality is a continuum; likewise, the art which mirrors it. For instance, my work titled “Crime Scene” is a case study on how the tradition is always part of an ongoing historical sequence. The work utilizes the famous pectoral mask of Queen Idia, part of artefacts looted from Oba’s palace in 1897 by the British soldiers, as a metaphoric premise for the brutal killing of George Floyd, which reignited the Black Lives Matter movement. However, the contemporary appropriation of the mask substitutes Portuguese heads with the faces of extra judiciously murdered blacks in the US. The piece travels across time to interrogate issues of slavery, colonialism, racism, and migration, among others.

TAYO: Your first international solo exhibition, titled “The Change We Need,” was staged in the US in 2015. What was the motivation behind this, and has the nation got the “change”?

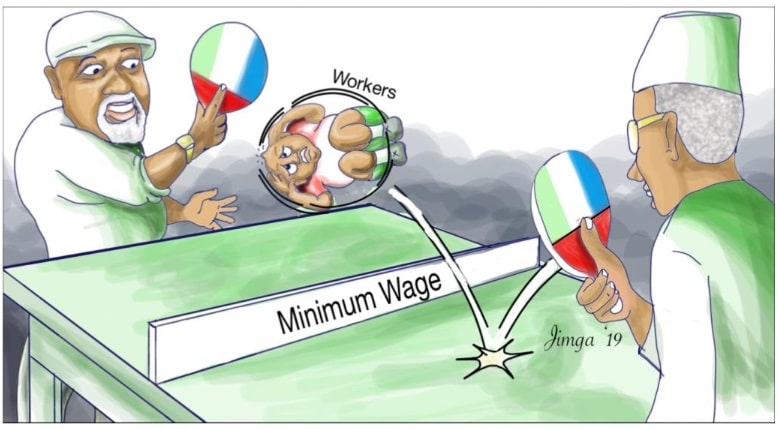

Jimga: As Chinua Achebe, author of Things Fall apart stated, “when a society is ill, the artist has the right to point it out.” The tensed socio-political realities of the period leading to the 2015 general election resulted in the clamour to remove the then Africa’s largest political party – the People’s Democratic Party. The exhibition featured cartoons reflecting the deteriorating standard of living of the commoner and the high level of corruption, nepotism, and insecurity. However, despite the change of government and prominent political actors, eight years after, the polity is still engrossed in the problems leading to the reason for the clamour for change in the first place. I do not believe the call was invalid anyway; the present situation just reminds us that the country needs a total overhaul and not fixing. In a situation where politicians could switch political parties like caps and not based on ideology will lead the country nowhere. With the knowledge of hindsight, the change Nigeria needs now is overhauling the actors with young fresh minds and strong ideology to move the county forward.

TAYO: As a scholar of art, how do you saddle the divide between being a practicing cartoonist and an art historian and art critic?

Jimga: I started as an artist before getting engaged in the theoretical aspect of art – art history and criticism. Being a scholar-artist has helped me understand the creative part of artistic production in my writing about art. I engage on a different theoretical level when it comes to analysis because it is not what I assume but what I live as an artist for. The knowledge of art history and its theory also contributes immensely to the way I employ imageries in my works. My recent cartoons have been grossly historical and experimental owing to the scholarly knowledge of what could and may not work as a practical strategy in art and political activism. I brought my theoretical knowledge to bear on my practices and vice versa.

TAYO: Do you have any favourite among your works? Which one will you choose as your favourite or the best of the lot?

Jimga: Interestingly, I do not have any work that is like “best work” for me. I see these works as pages of difference but interconnected texts of my reflections, interpretations, reactions, and appreciation of my realities. However, there is one that I can say I’m viscerally connected with. It is titled #Endsars. It was produced against the backdrop of the protest against police brutality in Nigeria in October 2020. The production of the work was cathartic to my feelings after the despicable killing of the EndSars protesters at Lekki Toll gate on October 20, 2020. The claim by the Buhari government that no killing took place was nothing short of emotional brutality. As an activist who was also part of the protest, I felt sad. I lost hope in the country’s future since that night until I was able to purge the melancholy through the cartoon. In the work, I related the EndSars protestors’ killings to the 1976 Soweto massacre of school children by the Apartheid regime of South Africa.

TAYO: What is the focus of your second doctoral research in the United States of America, and why is this so?

Jimga: I am extending the frontiers of my knowledge in cartooning to the study of digital art and animation. From my preliminary research on the subject, I discovered, that this area is less researched, especially from the perspective of Africans and the African diaspora. It is essential to explore digital expressions against the backdrop of contemporary virtual forms of socialisation, politicisation and neo-colonisation. The significance of authenticating digital art through blockchain technology and its generic implications are also of significant interest to my research. Blockchain technology has come to disrupt how we frame, interrogate and contextualize digital art globally. How might we reconstruct digital art pieces and foreground authenticity and provenance in the light of new technology? How can we deploy this technology in the ownership and repatriation discourse? These are questions seeking scholarly research.

TAYO: So, do you believe that NFTs have an impact on art?

Jimga: Before NFTs, which are actually a unique record of an image’s metadata on the blockchain technology, digital arts were confronted with two main constraints: fungibility, that is, several copies could be made with no distinction between the original and copies; secondly, it was near to impossible to trace provenance – who owned what at a given period. And interestingly, these are what make art valuable – nonfungibility, scarcity, and provenance. With blockchain technology, digital arts provenance could be established, and authenticity protected. Though lots of research still need to be carried out on this since it’s still an emerging technology but so far, I will advise artists to join the wagon which has come to disrupt our notion of art in a positive light.

TAYO Fatunla is an award-winning Nigerian Comic Artist, Editorial Cartoonist, Writer and Illustrator is an artist of African diaspora. He is a graduate of the prestigious Kubert School, in New Jersey, US. and recipient of the 2018 ECBACC Pioneer Lifetime Achievement Award for his illustrated OUR ROOTS creation and series – Famous people in Black History – He participated at UNESCO’s Cartooning In Africa forum held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and the Cartooning Global Forum in Paris, France and has held a virtual OUR ROOTS cartoon workshop for SMITHSONIAN- National Museum of African Art, Washington D.C. His image of Fela Kuti is featured in the Burna Boy’s mega-Afrobeat hit song “Ye”. –– [email protected]

We Publish News 24/7. Don’t Miss A Story. Click HERE to SUBSCRIBE to Our Newsletter Now!