*Proverb chapter thirty-one verses eight and nine reads, “speak up for those who cannot speak from themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute.

*Proverb chapter thirty-one verses eight and nine reads, “speak up for those who cannot speak from themselves, for the rights of all who are destitute.

Speak up and judge fairly, defend the rights of the poor and needy,” Bryan Stevenson is the true embodiment of this poignant proverb.

Stevenson, a Harvard Law graduate, founded the Equal Justice Initiative in 1989 and as their website states EJI is “a private, 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that provides legal representation to people who have been illegally convicted, unfairly sentenced, or abused in state jails and prisons.

We challenge the death penalty and excessive punishment and we provide re-entry assistance to formerly incarcerated people.”

From the day EJI first opened its doors until the present, under the tutelage of Stevenson, EJI has won reversals, relief, and release of 140 exonerated individuals off of death row. He has disputed and won numerous cases at the United States Supreme Court, such as the 2019 ruling defending condemned inmates who have dementia. He challenged life sentences without parole as an unconstitutional sentence for children, 17 and younger, in a landmark 2012 ruling. As Stevenson states in an EJI video, he disturbingly points out that the United States is the only country in the world that condemns children to die in prison even as young as 13 years of age. In 2005, the United States Supreme Court banned the execution of children and in 2010 he was able to persuade the U.S. Supreme Court to ban life imprisonment without parole for children convicted of non-homicidal crimes which also resulted in the Courts banning mandatory death sentences in prison for all children. One can only imagine if Bryan Stevenson was alive to defend George Stinney Jr., a 14-year-old African-American boy executed on June 16, 1944, in the Jim Crow South Carolina for the murders of two young white girls. No witnesses were called in the Stinney case, he had ineffective counsel representing him, and the young child was undeniably was coerced in admitting to committing the heinous crime. Stinney’s conviction was vacated 70 years later on January 2014 by a judge who concluded: “I can think of no greater injustice.”

Stevenson has championed for those on death row citing the factors that result in wrongful convictions in death penalty cases like racial bias, erroneous eyewitness identifications, false and coerced confessions, inadequate legal defense, false or misleading forensic evidence, false accusations or perjury by witnesses who are promised lenient treatment or other incentives in exchange for their testimony, and illegal racial discrimination in jury selection. Stevenson asserts the system “treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent.”

Consider Ethan Couch then 16, on June 15, 2013, who killed four people when he was driving drunk, speeding at 65mph in his father’s Ford F-350. His legal team disclosed that the irresponsible teen suffered from “affluenza,” which Merriam-Webster defines as “a social condition that arises from the desire to be more wealthy or successful. It can also be defined as the inability to understand the consequences of one’s actions because of their social status and/or financial privilege.” Couch received ten years of probation but violated it when he was caught at a party surrounded by alcohol and bolted to Mexico with his mother to avoid punishment. In 2018, Couch was released from prison after serving a two-year sentence.

Another example of how fractured our judicial system operates would be the case of Raimundo ‘Ray’ Atesiano the former police chief in Biscayne Park, a small South Florida city. Atesiano is serving a three-year sentence in prison for his role in framing black males for crimes they did not commit. Prosecutors said the crimes black people were falsely arrested for included burglaries and vehicle break-ins. In February 2014, Artesiano instructed one of his officers, Guillermo Ravelo, to apprehend Erasmus Banmah for five unsolved vehicle burglaries even though there was no substantial evidence that Banmah had committed the crimes according to the statement of the prosecutors in the court records. Ravelo had completed five arrest forms wrongly accusing Banmah of vehicle burglaries at five different street locations in Biscayne Park, as reported by the Miami Herald. During Atesiano’s tenure as police chief, the department had reportedly solved 29 of 30 burglary cases, but 11 of those cases were based on false arrest reports, proven by federal authorities.

“He fabricated evidence. He damaged lives. Even before he was chief, Atesiano issued 2,200 traffic tickets himself in one year, fabricated cases, and wrongfully arrested innocent individuals,” Miami-Dade Public Defender Carlos Martinez said. “He created a culture of corruption that has further eroded public trust in the criminal justice system. Just as appalling are the damage Atesiano has done to law-abiding, hardworking, police officers and chiefs.” Atesiano was not held culpable of violating the civil rights of the men he falsely arrested because his attorney argued that the men already had a history of criminal activity. Despite the Miami Herald attaining internal public records that suggested otherwise. One cop admitted during an internal probe in 2014 that the disgraced police chief ordered and pressured Biscayne Park officer to arbitrarily target black people to clear cases.

“If they have burglaries that are open cases that are not solved yet, if you see anybody black walking through our streets and they have somewhat of a record, arrest them so we can pin them for all the burglaries,” said one cop. “They were basically doing this to have a 100% clearance rate for the city.”

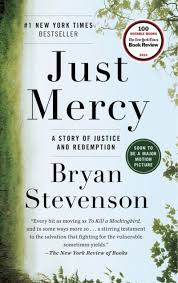

Anybody at any time can easily fall victim to our judicial system without any oversight to confirm the accusations are legitimate. Every other day a story will post on social media of another African-American man exonerated from prison because his case was flawed from the beginning. Bryan Stevenson and EJI are severely necessary in these present times where law enforcement can say or do anything to the poor and minorities, and their word, no matter how erroneous, can be taken as truth. The striking statistic Stevenson points out in his book, a New York TimesBestseller Just Mercy, that in the 1970s, approximately 300,000 people were imprisoned, today 2.3 million people make up the prison population with 6 million people on probation or parole. He also goes on to argue that “one in every fifteen people born in the United States in 2001 is expected to go to jail or prison; one in every three black male babies born in this century is expected to be incarcerated.” Also, to further provide injury to insult, the funding provided to jails and prisons by state and federal governments is astronomical; Stevenson states the price tag in 1980 was $6.9 billion today our government shells out $80 billion to build jails and prison. Private prison builders and prison service companies lobby for the creation of new crimes and to impose harsher sentences so that more people can be locked up thereby allowing them to earn more profits.

Stevenson knows the system is hemorrhaging and has set his life’s work to bring these injustices to the forefront of the American consciousness. His EJI offices are set in Montgomery, Alabama only five minutes away from the Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church where the revered civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. used to preach. Undoubtedly, Stevenson evokes the spirit of the late Dr. King as he has become this generation’s voice for the voiceless, marching before the Supreme Courts to dispute laws and practices that encourage the disenfranchisement of the most vulnerable in our society. His courageous and selfless efforts have not gone unnoticed; in 2000, Stevenson received the Olaf Palme Prize in Stockholm, Sweden, for international human rights. In 2003, the SALT Human Rights Award was presented to Mr. Stevenson by the Society of American Law Teachers. He was awarded the NAACP William Robert Ming Advocacy Award and the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Fred L. Shuttlesworth Award. In 2016, he received the American Bar Association’s Thurgood Marshall Award, and in 2018, he was awarded the Martin Luther King Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize from the King Center in Atlanta. He was honored with 40 honorary doctoral degrees, including degrees from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and Oxford University. His critically acclaimed New York Times bestseller book, Just Mercy, was named by Time Magazine as one of the 10 Best Books of Nonfiction for 2014 and was awarded several honors, including the American Library Association’s Carnegie Medal for best nonfiction book of 2015. He created two highly acclaimed cultural sites which opened in 2018: the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. These new national landmark institutions chronicle the legacy of slavery, lynching, and racial segregation, and the connection to mass incarceration and contemporary issues of racial bias. His 2012 Ted talk, “We need to talk about an injustice,” held the record for the most extended standing ovation. With the release of the film Just Mercy, based on his experience of representing his now-deceased client Walter McMillian, Bryan Stevenson will undoubtedly become a household name.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu described him as “America’s Nelson Mandela,” Michael B. Jordan who plays him in the film said he is a real-life superhero and as it is known not all superheroes wear capes. Stevenson is a man that has a nature of quiet confidence, he speaks softly and patiently, but while he has the meekness of a lamb, he has the spirit of a lion. We had to chance to talk fittingly on the birthday of Martin Luther King Jr. while he was in the middle of the U.K. promotional tour of Just Mercy to discuss how the film may affect change in our current judicial system.

Just Mercy stars Jamie Foxx as Walter McMillian, one of Stevenson’s first clients. McMillian was accused of killing 18-year-old dry-cleaning clerk white woman Ronda Morrison in 1986 in Monroeville, Alabama even though many witnesses placed him at a church fish fry.

I read your book, and I had to put it down several times because it was so heart wrenching. What was your purpose of humanizing the individuals on death row?

I read your book, and I had to put it down several times because it was so heart wrenching. What was your purpose of humanizing the individuals on death row?

I wanted to challenge this idea that people are just crimes. The policy debate in America, when you hear politicians talking about criminal justice issues, they talk as if they can put crimes in jails and prisons. They create these extreme penalties these and these extreme punishments that they’re going to put the crime in prison, but we don’t put crimes in prison we put people in prison, and I believe that we are all more than the worst thing that we’ve ever done.

I don’t think if someone tells a lie they are just a liar or if someone kills they are just a killer. I [wanted to] expose the unreliability, the unfairness of our system. We have a system that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent. Obviously, we know that we live in a nation that has not overcome the burden and the bigotry that has been created by our history of racial injustice in the presumptions of dangerousness and guilt that get assigned to black and brown people. It is something that we have not acknowledged or addressed with near the kind of commitment that is required, so all of that was part of the motivation in writing the book.

Throughout your book, you masterfully showed the correlation between America’s racial history as it impacts our current judicial policies and the criminal system as a whole. How can this system be changed since it’s so ingrained in the racial bias of this culture?

Well, I think first of all we have to address it broadly even outside of this system. We have to do more to acknowledge this history of racial bigotry. We are a post-genocide society in America we haven’t acknowledged what we did to Native people when the Europeans came. We haven’t confronted the legacy of slavery, the great evil of slavery wasn’t involuntary servitude it was this idea that black people aren’t as good as white people, that we’re not fully human, we’re not evolved, and that ideology of white supremacy has never really been acknowledged or confronted. That’s why I’ve argued that slavery didn’t end in 1865 it just evolved. We haven’t talked about the damage done by decades of lynching and racial terrorism even segregation I started my education in a colored school as a little boy I couldn’t go to the public school.

There were no high schools for black kids when my dad was a teenager and all of this stuff creates a weight of injury this smog in the air in America created by our long history of racial bias so we’ve got to deal with that. At EJI, we’ve now opened a museum [depicting] slavery to mass incarceration; we’ve built a memorial dedicated to the victims of lynching and segregation. For me, that work is critical and is necessary in confronting the issues that we see in the criminal justice system, but I do think there are things we can do there as well. Too many people in the country don’t even know who their prosecutor is; they can’t name the sheriff or the chief of police we wait until there is a crisis before we begin to engage with these people and I think that has to change. There are immunity laws that shield police prosecutors and judges from accountability; I think those laws need to change.

I would love to see advocates and activists start identifying these kinds of reforms as critical in the way to create a different system. If we do both of these things, talk about the larger narrative of racial justice and focus on specific reforms I think we can actually create an environment where things are safer, healthier for both the poor and people of color.

You worked with Ava Duvernay on her documentary 13thand you made a comment that there needs to be a canon of films that highlight slavery, lynching, mass incarceration, and the prison industrial system. With the success of When They See Us and new movies like Just Mercy and Clemency, why do you think it’s important to have a canon of films that address these difficult topics?

I think art and cinema are powerful tools that shape culture and changing the way we think about issues. We have 100 films about the Holocaust and I think there’s a conscious of the wrongfulness of what happened in the mid-20th century that is really necessary in building a resolve, a commitment to never again allowing that to happen. We haven’t done the same thing for confronting our history of slavery, lynching, and segregation, and we need to do that. Too often we have films that touch on racial inequality we tell the story in a way that is so sugar-coated or that some white person who solves all the problems or fictional narratives about what happened and I just think that that’s dishonest if we had a canon films that told the truth maybe you could have a story that manipulates these realities but we don’t. I think films like When They See Us, films like 13th, films Clemency, films like 12 Years a Slave, become important because there are so few given the enormity of this problem, which is why more films like Just Mercy are made.

I’ve told people I want them to see it not because it is an important story but I want films like this to succeed so that there’s more pressure on studios and filmmakers to tell our stories more honestly. There is an absence of stories and films about slavery, lynching, or even segregation and you realize there is a real void in cinema today particularly in America with these things have been so dominant and yet so under-examined, under discussed.

The case of Walter McMillian took place in Monroeville, Alabama, the same town that renowned book To Kill a Mockingbird written by Harper Lee was set. It was such an interesting juxtaposition of the story and what you were dealing with Walter McMillian’s case. What were your thoughts during that time and how is it the citizen of that town, who celebrated the book but could, not see the parallel of a real-life situation to what occurred in the book?

Well, it was bizarre to me because if you go to that community, they are preoccupied with that story. They identified so strongly, they’re so proud of their association with the story. The characters of the book have streets named after them, and I do think that is a microcosm of what we do with America. We have a constitution that talks about equality and justice for all. We pat ourselves on the back about having the best system in the world. We have all of these patriotic songs that extol our virtues as a society and yet we have tolerated such injustice, inequality, such bigotry such abuse of power when it comes to the poor and people of color.

That’s why I felt like this case was such an interesting case to develop into a story because until we recognize that our rhetoric, our words about freedom, justice, and equality have no meaning if we are not committed to them when it comes to helping the poor and the disfavored. I’ve said this before I don’t think our society is going to be judged by how we treat the rich, the powerful, and the privileged, we are going to be judged on we treat the poor, the neglected, and the incarcerated. That’s the truth of what has to be lifted up in our country and exposing the disconnect between To Kill a Mockingbird and what happened to Walter McMillian was important to me.

Michael B. Jordan plays you in the film Just Mercy, what advice and insight did you give him on what you were dealing with during Walter McMillian’s case?

I was so honored to have him in the role; he’s talented and gifted. I think the thing I wanted him to appreciate is that you have to be persuasive, you have to prevail, and you have to be strategic and tactical. If it just took anger, if it just took emotion we would have gotten justice a long time ago, that’s not sufficient. It was important to me that he played the role with an awareness that [no matter how] bad things were for me, it was so much worse for my client. I could’ve refused to submit to that strip search, got in my car, and gone home, but my clients can’t do that. That is why it was important to suffer through some of those experiences to be tactical in the face of that kind of humiliation and abuse because I know that I’m fighting for people who are even more vulnerable than I am.

He seemed to get that, and I appreciate his embrace of that because that’s not an obvious choice for an actor, a lot of times you see these roles where people are making loud statements, and I just don’t think that’s effective in the world that I operate in and he embraced that and I thought he did a good job in the role.

During the film, Jaime Foxx was captivating as Walter McMillian displaying fear, hurt, and disappointment with just his eyes. What did you discuss with Jamie Foxx about Walter McMillan because he was able to tap into the spirit of Walter McMillian even though he wasn’t given the opportunity to meet him?

Exactly, it’s an amazing performance; this is an extraordinary performance by Jaime, he deserves more recognition because he inhabited Walter and you’re right he’s such an incredibly skilled actor you see the fear, the frustration, the anger, the relief. I loved his performance and I spent a lot of time with him. He did a beautiful job of presenting the humanity of my client, the dignity of my client, their aspirations, their hopes, and their fears. What excites me is that I’ve always wanted people to see what I’ve seen, I’ve always thought if people saw what I see on a regular basis they would want the same things that I want. They wouldn’t want to see people treated unfairly or unjustly and through Jamie’s powerful performance as well as Rob Morgan, who is also amazing in this [film]. People can leave the theater now aware of the horrible things we are doing to people in our jails and prisons and I’m so grateful for Jamie and kind of performance it’s really one of the best things about the film.

Today is Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s holiday to commemorate his efforts in the civil rights movement. You commented that for people to change this system they need to close to the problem. Can you expand on that because MLK did get close to the problem of racial oppression and inequality? How do you suggest we continue to honor his spirit in regard to mass incarceration?

I do think we have to get closer to people, so many people have been silent about this phenomenon. There are 132 million people in America with loved ones in jails and prisons, and we don’t talk about it. But we’ve got to go into the jails and prisons, we’ve got to help people coming out of jails and prisons, we’ve got to get closer to the poor, the neglected, the marginalized, there is a segment of the African-American community that is able to create distance from a lot of these issues. During the Civil Rights era people put on their Sunday’s best and they went to places where they were going to get bloody, brutalized, and beaten because they believed in civil rights.

They didn’t have to do it, but they did it anyway, and so for me, it is necessary that we get proximate. I think we have to change these narratives that got to confront the presumptions that gauge guilt for black and brown people have to navigate. I think we have to stay hopeful, I do believe that hopefulness is the enemy of justice; hope is our superpower. I think we have to be willing to do uncomfortable things because we can’t change the world, we can’t increase the justice quotient if we are unwilling to do things that are uncomfortable the world doesn’t work like that if people do that I am persuaded that we can see change. We’ve seen some change but we can see more change if more people are engaged in getting, getting proximate to the problem, changing the narrative, staying hopeful, and doing the uncomfortable things.

What gives you hope to keep going because sometimes you lose some clients as detailed in your book. How do you maintain hope when you’re dealing with a goliath of a problem?

I’m lucky to live in Montgomery to live in a place where the memory, the witness of the people who came before me, is all around. I stand on the shoulders of people who did so much more with so much less. They had to frequently say, “my head is bloody but not bowed,” I’ve never had to say that.

I think about the people who came before me. My great grandparents were enslaved in Virginia. My great-grandfather learned to read as an enslaved person even though he had every reason to doubt that he would ever be free, that he would ever be able to use that skill, yet he had that conviction. My grandmother fled the south during the time of lynching and terror because she had this belief that she could bring another generation into the world that would have greater opportunities. My parents endured the humiliation of segregation and had enough love to create my siblings and me. I just want to honor that we were poor but my mom went into debt to buy the World Book Encyclopedia so we would have a portal to a larger world than the world we saw in our racially isolated community. When I think about their struggle, their sacrifice, and the hope that they had to have to endure all those things I just feel like it is my obligation to be hopeful; to keep fighting to keep pushing, to stand up even when they say sit, to speak even when they say be quiet.

That’s really what animates me and now that we have our museum and memorial in Montgomery, I’m really inspired by the reactions to those spaces have created and I walk through there sometimes just reflecting on all of the enslaved, all of the terrorized, all of those who were segregated. I hear them saying keep fighting, and that’s really empowering to do the work that I do, and I rely on that heavily when I have those difficult moments.

Explain how people can get involved with your organization, the Equal Justice Initiative?

Well if they will go to our website, Eji.org we have several pages dedicated to how you can get involved and we will connect you to organizations working in your community that are doing reentry work or providing services to people in jails and prisons.

We invite people to come to Montgomery to spend time at our site, and we think that’s an important way to dig deeper. We have a lot of resources on our site; we have calendars that educate people about the history of racial injustice. We have reports in the literature that educate people about slavery, lynching, and segregation. We have campaigns that highlight where people are asked to get directly involved in issues that are coming up for votes; we have other discussion guides people could organize conversations around the film Just Mercy and the documentary True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality we did earlier with HBO.

So there are lots of ways people can get involved no matter where they live, no matter what their status is, whether they’re in school or whether they’re a teacher or older and I hope people will go to our site and connect with us.

What is the biggest takeaway you want the audience to leave with when they see Just Mercy?

I want to believe that we are all more than the worst thing we’ve ever done. I want people to remember just because somebody tells a lie they are not just a liar. Just because of commits a crime they not just a criminal. There is a need for us to create space for redemption and recovery. I also hope people will take away from this is that our system is a reflection of our inaction that means we have to get active and lift our voices, we’ve got to vote, and we’ve got to become more consistent in holding people accountable for the kind of systems that we have. I don’t think anybody could see this film and be moved by it and then decide not to be active in the upcoming elections. This is a critical time in American history, and we all have to be active and vote.

Follow @JustMercyFilm on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook.

We Publish News 24/7. Don’t Miss A Story. Click HERE to SUBSCRIBE to Our Newsletter Now!