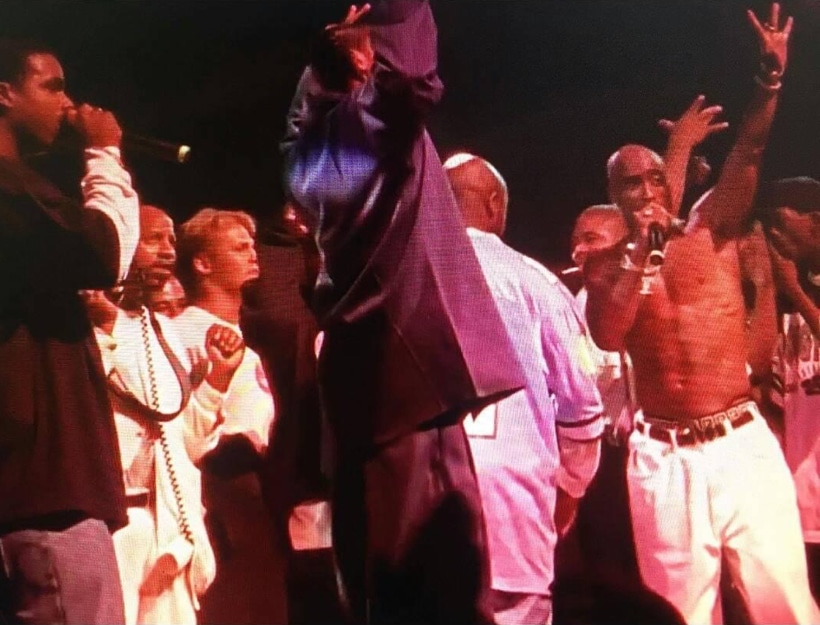

*It’s been 25 years since the show that changed Rap. A lot of life has happened since then. A lot of death too. It was a moment that defined a genre, that catapulted a genre into a new space. And for some insane reason I was a part of it.

Many stories have come out about that day. This is my story. It’s a story of the day and of my interactions with Tupac Shakur. It’s a story of the politics of the time and the build-up to the show. It’s a story of how the show almost never happened. I mean, really, the biggest show in Rap history almost never happened.

My name is James Farr. Let me explain.

The days leading up to the show

We had been in talks for what must have been months but every time it looked like we were making headway we were shut down again. We wanted it, Suge wanted it. Tupac, Snoop, and all the other artists wanted it. But the politics and fear around this concert were unreal.

Back and forth we went. It was my boss, Andre Farr, CEO of the House of Blues Sports Division, and I who were really pushing for this event. But we could not get approval. No matter which way we turned we got shut down. It didn’t help that Tupac was out on bail and all these different magazines were coming out with stories of the East Coast/West Coast deadly rap beef. The threat of violence was real and many of the higher ups were justifiably scared.

You see, Marion “Suge” Knight and Death Row Records had a reputation. Suge’s giant-like and imposing presence struck a fear at all levels. He and Death Row were part-bully, -thug, -gangster, and -goon, especially when it came to business. A few years before the event I had witnessed a group wearing the Death Row Diamond Chains beat the shit out of someone outside the Comedy Store after a Phat Tuesday’s Show. Chris Tucker was performing. He was getting heckled by someone in the audience. The guys that identified themselves as Death Row beat someone they thought was the heckler. There was an attack on another innocent bystander too. As far as I could tell it was unprovoked. They left, returning shortly after and shooting at the guy as he lay unconscious. Luckily his friend pulled him away just prior to the gun shots. The stories of Death Row’s ruthlessness were no secret; and nobody wanted to find out if they were myth or truth.

RELATED NEWS ON EURWEB: Mike Tyson Explains Why He Feels ‘Guilty’ Over Tupac’s Death [WATCH]

The thing was, while the threat of violence was real, so was the use of that threat as a scare tactic. Rap was being stifled because of that fear. Great music was being stifled. Tupac was being stifled. We were being straight hated on.

I should probably clarify. When I say rap, I mean West Coast Gangsta Rap. The kind of rap Tupac was performing. Rap and Hip Hop were nothing new – we were just coming out of the golden age of Hip Hop. But the kind of rap Tupac and others were doing? No way. West Coast Gangsta Rap was Black. It represented the voice and narrative of the inner-city, it told real stories and was a counter to the bubble-gum pop music culture. It was well on its way to becoming the dominate cultural influencer.

It was real and raw. And it was often seen as violent, plagued with irrational behavior, resigned to ratchet clubs and small venues where shit went down almost every night. Aggressive, volatile, charged with energy, many thought this genre of Rap had no place in the House of Blues. The House of Blues was the pinnacle of LA music at the time. You play here and you’re accepted, you’re in.

And this stuff was not in.

I remember a board meeting. I was 22 but looked 16, fairly new to the LA scene and juggling a million and one responsibilities alongside people who didn’t think I should be there. Just a kid from the Bay who loved all kinds of rap music, the kind of kid whose knowledge of Bay Area rap was deep. Real deep.

In this board meeting we were sitting there, arguing our case. We weren’t stupid. We knew the risk, but we also knew that so much of what kept rap in the background was fear. Rappers didn’t usually look like most of the people that sat in that board room, didn’t have the same color skin. So it didn’t matter that we had taken every precaution. It didn’t matter we were hiring something like one hundred extra security for the event.

It was in that meeting that storms collided. There was a palpable fear in the staff of the House of Blues. And to make matters worse, a few days earlier a few staff members had been involved in a fatal car crash following a beach party.

Anxiety was high and we were told that many of the front of house staff felt nervous and uncomfortable. They weren’t going to work the event. Many flat out refused to work the event.

Well that was it. The final straw. I hung my head low. It was a wrap.

Until it wasn’t.

Isaac Tigrett stood up. Founder of the House of Blues and lover of music, Isaac didn’t buy the scare tactic. He took a stand.

If people didn’t want to work, they didn’t have to. We would find other people. We would make it work. I remember he reminded his employees of their motto: help ever, hurt never. We would make it work. This show was happening. It needed to happen.

And just like that we were back on and everything got real.

Enter Roy Tesfay. Roy was quarterbacking the plays for Death Row. His official title was probably something like Suge’s Executive Assistant but he did everything. He was the direct line to the label and couldn’t have been much older than me. There was a comradery between us, even though we were working for different camps. We both performed similar functions within our camps. We both had bosses that expected to get what they wanted, how they wanted, when they wanted.

Roy was smart. I mean whip smart. At Death Row there were gains and rewards for getting it right but there were consequences for getting it wrong, getting anything wrong. I remember in conversations listening to him as he thought out loud. It was as if he needed to stay two or three steps ahead, always ready, always aware.

“All I remember was you saying is we have to get this done,” said Roy in a conversation 25 years in the making. I hadn’t spoken with him since the show. Over the years I often thought about him and was surprised whenever I didn’t see him in one of the many documentaries and articles around Death Row. By now I’d have assumed he’d be one of the top music executives in the industry. He was never one for the limelight. Like me, he didn’t seek notoriety. Instead choosing to fade away and as far as I’m aware only appeared in a recent FX docuseries Hip Hop Uncovered.

But during that time Roy and I felt like co-conspirators. We both worked 24 hours a day in an industry that never slept. We were constantly picking up what people were throwing at us. We were in a head on collision at the intersections of the Streets and the Suites. And we both knew we couldn’t fuck up. Consequences were dire if we fucked up.

This meant coordinating with Queenie at the label’s studio, fielding numerous requests from Poppa George, the head of the label’s PR, and working out production logistics with Kevin Swain who would film and later release the famed Tupac Live from the House of Blues video.

Get the rest of this story about Tupac Shakur’s first and last rap concert at The House of Blues on July 4, 1996 by James Farr at Culture Honey.

We Publish News 24/7. Don’t Miss A Story. Click HERE to SUBSCRIBE to Our Newsletter Now!